Trappers went north with dreams of many furs, of freedom, of adventure in magnificent surroundings. Fox and polar bear pelts provided income, whereas Svalbard reindeer and rock ptarmigans provided welcome additions to the menu. Trappers worked constantly during the summer, but the dark winter months could mean a life in total isolation. The animals they hunted followed the same annual rhythm. Sunlit summer is the time for reproduction, but activity slows in the dark season. Whereas animals do all they can to prevent loss of body heat, some trappers’ cabins show that their inhabitants were less skilled at staying warm.

OVERWINTERING FUR TRAPPERS

In the late 18th century, the state monopoly on trade in Finnmark was abolished and trading towns were established. The economic conditions for merchants changed, in part owing to increased trade with the Pomors. Good connections with Pomors gave first-hand information about Russian trapping in Svalbard. Moreover, starting in 1784, Danish–Norwegian authorities promised incentives to vessels attempting to hunt in the northern seas. But the extraction of resources from Svalbard did not start in earnest until 1819. Knowledge of the Arctic’s bountiful resources combined with improved economic conditions gave impetus to land-based trapping in the archipelago.

The Buch trading company in Hammerfest equipped an expedition of fifteen men for the first Norwegian overwintering in 1795-1796. Four Russians went along to teach the Norwegians winter trapping. The activities followed Russian routines. There is no reliable information on additional expeditions until 1822. This time, the trappers also came from Hammerfest. Sixteen men spent the winter in Ebeltofthamna in Krossfjorden. A new trapping team took over in 1823, and the same year, another team wintered on Bjørnøya. Hammerfest was the most important city on the Arctic Ocean until the 1850s, after which Tromsø became the centre for all activities in the northern seas. By 1892 a total of 21 teams had spent the winter up north, of which 14 did so voluntarily. At the time, walrus was the main prey, along with seals and other animals with fur.

- 1/1

Seal hunting. Photo: Svalbard Museum

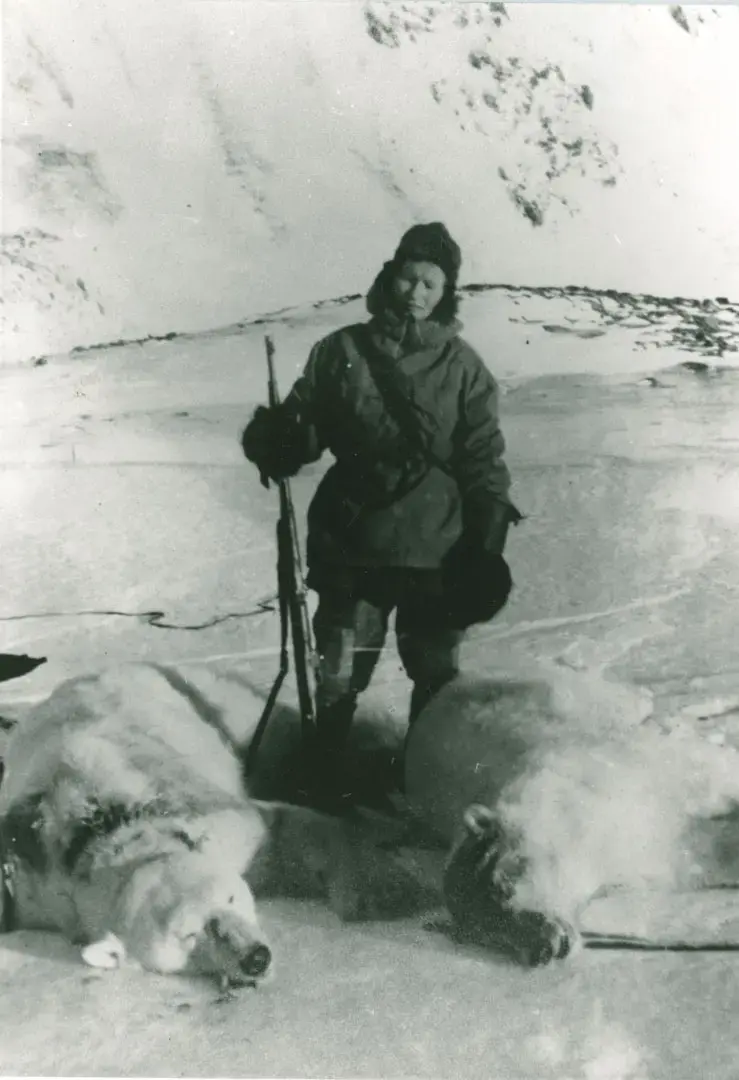

Overwintering fur trapping had its heyday from the end of the 1890s to 1941. Nearly four hundred people lived as trappers during that period, about 6% of them women, making a total of over 1000 winter seasons spent trapping. Winter trapping mainly involved taking pelts. Seal and bird hunting and collection of down also provided income.

The total monetary value of winter trapping between 1924 and 1940 was NOK 1.6 million. Seal hunting over the same period gave over NOK 41 million. Winter trapping had little economic significance. Nevertheless, it attracted attention, in what might be called inverse proportion to its economic relevance.

One question that arises is why some people left the mainland and embarked on an uncertain, isolated, risky existence in Svalbard. There were many reasons, but the desire to be one’s own master and experience adventure, along with the hope of selling many furs, may have been the main motivations. Helge Ingstad writes that the reason ‘had to do with humankind’s primal nature and need for freedom’.

SCURVY

Scurvy was feared by seafarers; for several hundred years it was considered fatal. Johan Hagerup wrote in his diary (1900-1901): ‘We are sort of afraid that if there’s too much rest and relaxation, that devil scurvy may soon pay us a call. Outside we have several Russians from times gone by who were visited by scurvy. There are enough skeletons outside our door.’

The disease causes lethargy, the gums swell up and bleed and eventually the teeth fall out. Scurvy attacks connective tissue. The bleeding and swelling spread to the rest of the body and ultimately lead to death. In 1923 it became clear that the disease was caused by lack of vitamin C. Previous experience had shown that scurvy could be prevented by consumption of the little herb ‘scurvygrass’ (Cochlearia officinalis) or cloudberries preserved in crocks and brought along from home.

Scurvygrass grows all along the Norwegian coast and also in Svalbard. It belongs to the Brassica family and grows to a height of 10-35 cm. It is rich in vitamin C.

THE HUNTING GROUNDS

Trappers set up a primary dwelling place – a cabin called the main station. In addition, most also had several small cabins – secondary stations – placed one or several days’ journey away from the main station. Between all these cabins, they set out fox traps and/or self-triggered rifle traps for polar bears.

- 1/1

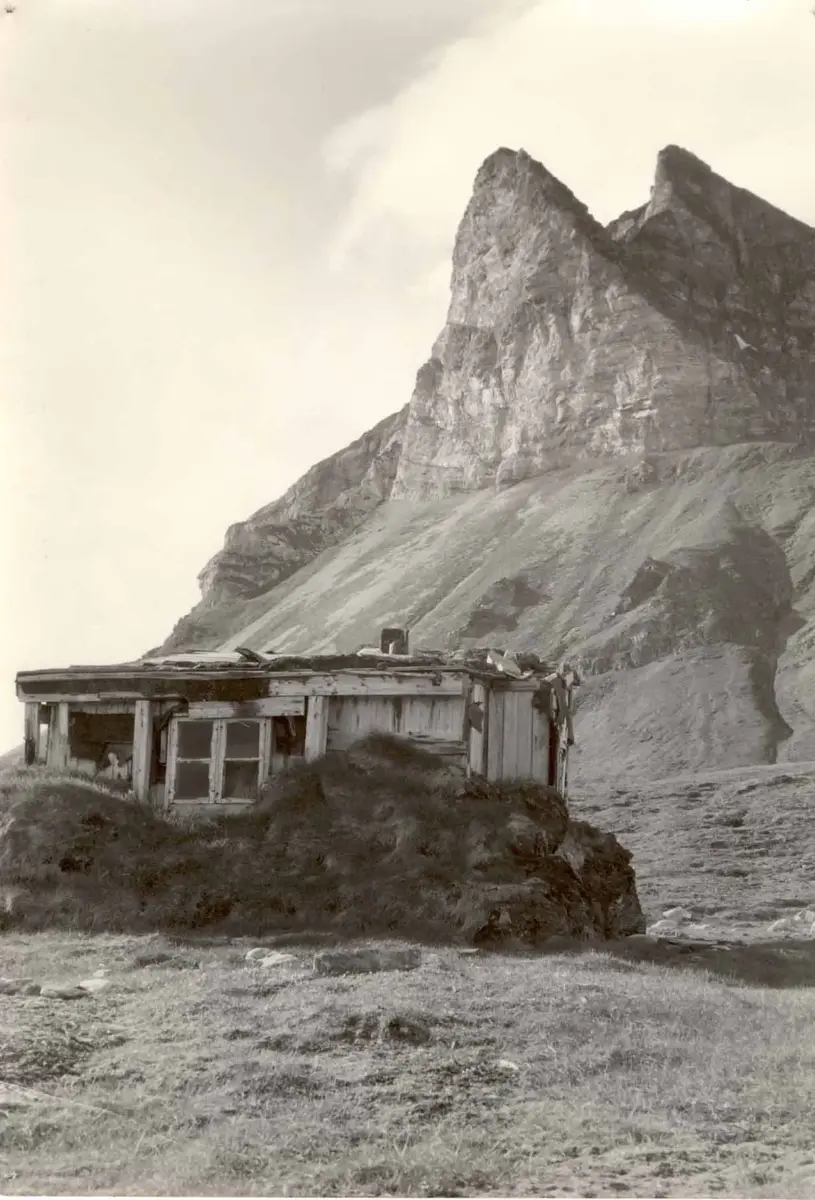

Derelict trapper’s cabin beneath Alkhornet. Photo: Norwegian Polar Institute

In fox habitats, trappers set up deadfall traps between the stations. Even though the entire hunting ground was used, most traps were placed in the lowlands. In late October, when the foxes’ fur was good and thick, the traps would be set. Every autumn, trappers gathered 30-40 kg of rock for each trap. If they were lucky, last year’s rocks would still lie in a neat heap near the trap. But curious polar bears often played with the traps, making repairs necessary.

- 1/1

Wanny Voldstad – Svalbard’s first female trapper. Photo: Svalbard Museum

In some places, deadfall traps and self-triggered rifle traps were used simultaneously. There, the landscape became a network of cabins and trapping gear, tenuously but indisputably connected by paths or ski tracks. In addition to capturing animals for their pelts, the trappers harvested every resource the Arctic terrain had to offer: seals, seabird eggs and down, ptarmigans and geese, and driftwood to use as fuel or building material.

Although overwintering trappers rarely became rich, they tried to harvest as much as possible during 10-11 months of the year. They had to survive every danger, endure isolation and loneliness, and return home alive and well, with enough goods to turn a profit.

DEADFALL TRAPS AND SELF-TRIGGERED RIFLE TRAPS

Deadfall traps were set up with the opening into the wind to prevent them from being filled with snow. The trap’s wooden panel measures about 1×1 metre. It is placed on the ground and propped up with a trigger mechanism consisting of two vertical and one horizontal stick. The bait – blubber or a ptarmigan head – is positioned at the inner end of the horizontal rod. Rocks are placed on the wooden panel. When a fox takes the bait, the trigger mechanism collapses and the panel falls onto the animal, killing it.

The self-triggered rifle trap for polar bears is the only trapping device developed in Svalbard. These were placed on promontories or hills so the wind would keep them free of snow, and so polar bears could spot them. A self-triggered rifle trap consisted of a sawed-off rifle positioned inside a wooden box on legs; string or wire connected the bait with the trigger. The traps used in Svalbard were designed by trapper Gustav Lindqvist around 1928. Self-triggered rifle traps were effective, and the method was quickly adopted wherever polar bears could be found.

- 1/1

Self-triggered rifle trap. Photo: Knut Bjåen Svalbard museum