Geological history

In Svalbard we find rock formations from essentially every geological era. Svalbard’s sparse vegetation makes it easy to see the layers of rock and trace their geological history. This has delighted geologists ever since the first Norwegian expedition in 1827, headed by Keilhau – the father of Norwegian geology. Svalbard remains a popular destination for geologists from all around the world. At present, the archipelago resembles a landscape emerging at the end of the Ice Age. It is barren, with little vegetation, and more than half of Svalbard is covered by glaciers that are still shaping moraines. The rivers sweep away rocks, gravel, and clay, forming flatlands in the valleys and deltas when they reach the sea.

Ancient rocks

The oldest rocks date from the Precambrian era (over 1000 million to 440 million years ago); they form Svalbard’s bedrock and consist of metamorphic sedimentary and volcanic rocks such as schist and gneiss, and igneous rocks such as granite. There are few fossils from Precambrian time. This is because the rocks have undergone significant metamorphosis, and because life on Earth was at an early stage of development.

Movement in Earth’s crust

Over 400 million years ago, Svalbard’s part of Earth’s crust was in motion. Mountain ranges were formed (the Caledonian Orogeny), and granite intruded into them. These granites now form some of the highest mountain peaks in Svalbard. Erosion over subsequent eons has broken down most of the mountain ranges.

- 1/1

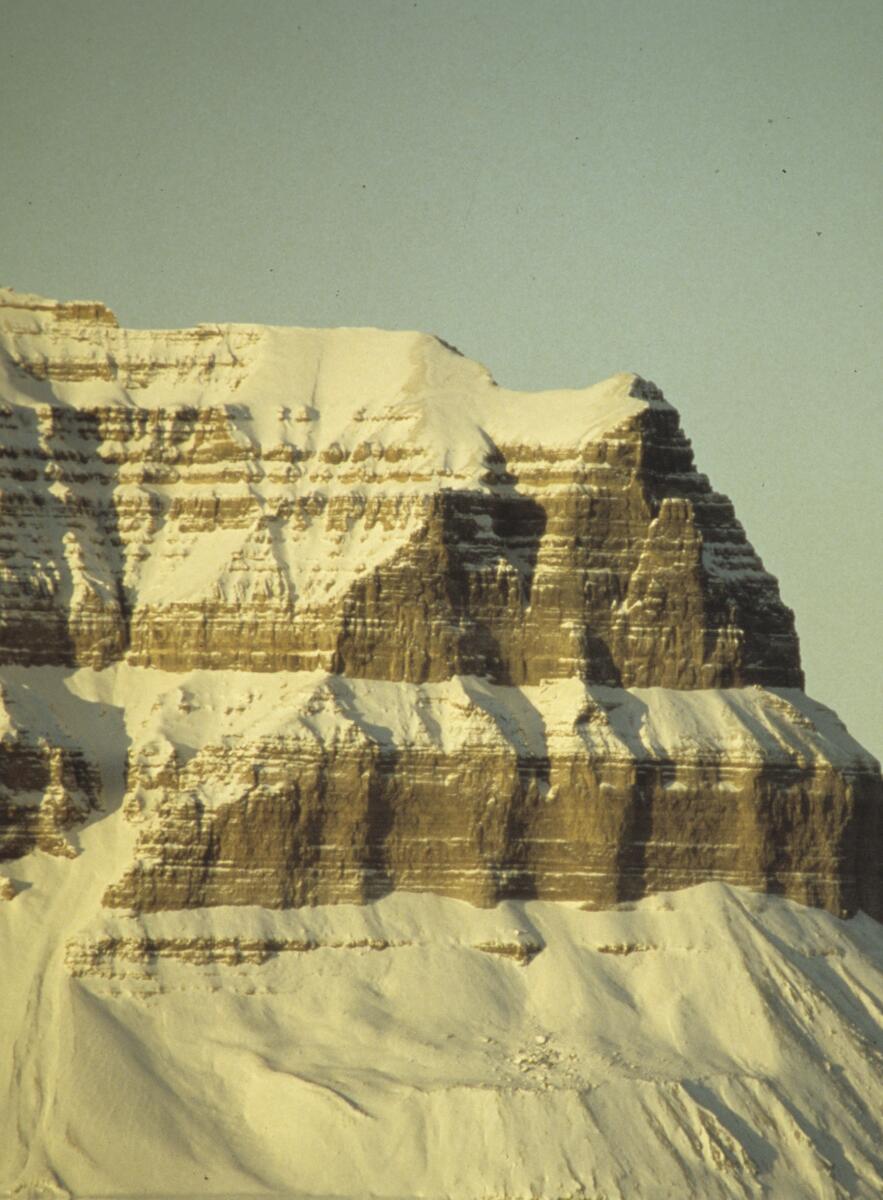

Tempelfjellet. Photo: Svalbard Museum

Devonian

After the Caledonian Orogeny came the Devonian period (about 375 million years ago), when central parts of Svalbard gradually sank. Layers of sediment several thousand metres thick were deposited. This occurred in a dry climate, partly on land, partly in fresh and brackish water. The oldest fossils of armoured prehistoric fish are found in Devonian rocks, along with fossils of primitive plants.

Carboniferous

The Carboniferous period was humid, and sediments were deposited in shallow seas and on low plains. Sand, clay, and the remains of plants in swampy areas gave rise to sandstone, shale, and coal. The sea flooded land areas 300 hundred million years ago, and layers of limestone, dolomite, anhydrite, and gypsum formed. Some of these layers are rich in marine fossils from the end of the Permian period (250 million years ago).

Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous

Svalbard used to lie much closer to the equator than it does at present. During the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous periods (250 to 65 million years ago) Svalbard moved from 50°N to 70°N. Its climate was temperate and humid. The rocks formed at this time alternated between being deposited on land and at sea and contain many marine fossils. In several places, volcanic activity led to intrusion of igneous rock (dolerite) into the strata.

Tertiary

During the Tertiary period (65 to 2 million years ago) powerful movement in Earth’s crust led to folding and mountain formation. Large swamps formed in the central parts of Svalbard. These swamps ultimately became the mighty coal seams of Longyearbyen, Sveagruva, and Barentsburg.

Volcanism

Over the past two million years, volcanism and ice ages have made their mark on Svalbard’s geology. Traces of 70 000-year-old volcanic eruptions and hot springs that remain active to this day bear witness to volcanism. During the most recent ice ages, rock several kilometres thick was worn away in many places, as glaciers gradually carved out the landscape we now know.

What is coal?

Millions and millions of years ago, over long stretches of time, dead plants and animals in Svalbard were buried under sand and mud before they had decomposed. The weight of the overlying sediments raised both the pressure and the temperature. Over thousands of millennia, the remains of the plants and animals were transformed into coal, oil, and gas. Peat bogs were compressed and turned to coal. They became ‘fossilised solar energy’ – captured through photosynthesis and preserved to our time. Such processes are still going on, but since they take such a long time, we call coal, oil, and gas ‘non-renewable energy resources’. Svalbard’s ice later wore away the uppermost rock layers and the coal seams lie near the surface. In some places they lie in plain sight.

- 1/1

A gypsum mine being established in Skansbukta, 1936. Photo: Anders Kjøde/Svalbard Museum