From the mid-1970s, Longyearbyen gradually evolved from a mining camp to a town for families. Normalisation of the local community became Norwegian policy. But what, precisely, had been so ‘abnormal’, and what did the new Svalbard policy entail?

Early in the 1970s, Store Norske was in crisis. Coal prices were low and the coal reserves were believed to be nearly depleted. The Norwegian government had to allocate huge sums to save the company from bankruptcy; in the end, the state essentially took over all the shares in 1976. This was in the middle of the Cold War, and it was vital to maintain Norwegian settlements and activities in Svalbard. Once Store Norske was owned by the state, it became politically unacceptable for Longyearbyen to remain a company town. In 1975 the authorities prepared to normalise the town, making it a place for families, with better social and community services. In 1976, the state took over the school – which had previously been run by Store Norske – and added secondary schooling. The hospital became state-owned in 1981. Postal and telecommunication services, and the Office of the Governor (Sysselmannen) were expanded. In 1981, Longyearbyen was connected to the Norwegian telecommunications network via satellite; direct television broadcasts started a couple years later.

- 1/1

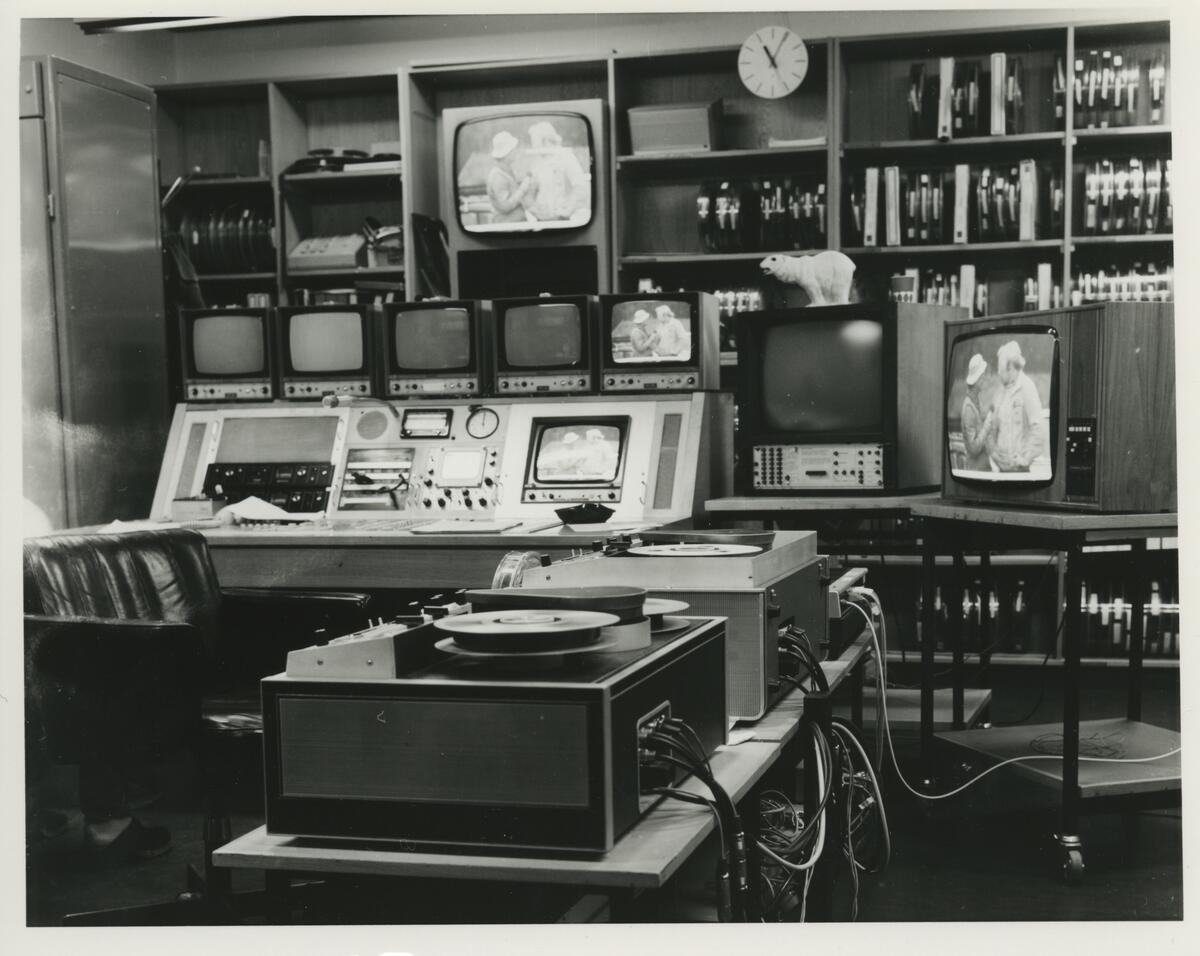

Picture from the TV-house in Longyearbyen 1969/1970. Photo: Svalbard museum

The airport – a turning point

One factor that made Longyearbyen ‘abnormal’ was that the town was effectively isolated for six straight months in winter. When the airport was built in 1974 and officially opened the following year, this marked a turning point in Svalbard’s history. Aeroplanes brought fresh food, newspapers, videotapes of television programmes, friends and family – but also influenza, bureaucrats, and members of parliament. The airport likely played the most important role in Longyearbyen’s modernisation. Better connections had both positive and negative effects. Many Svalbard veterans missed the sense of calm, stability, and togetherness that characterised Longyearbyen before the planes started landing.

Family community

In the 1970s and 1980s, many apartments intended for families were constructed; this meant that not only administrators, but also labourers employed by Store Norske could live with their families in Longyearbyen. The workers’ barracks in Sverdrupbyen and Nybyen gradually emptied, and in 1985 Stormessa – the main mess hall – closed. The houses constructed in Lia created a completely new neighbourhood in Longyearbyen. Government agencies arranged for their employees to bring their families along. Even though men made up the majority of Longyearbyen’s residents until the 1990s, the proportion of women and children steadily increased. This put its stamp on the community. Feminine values grew more prominent. Longyearbyen’s character changed: a city centre evolved, with a post office, a bank, shops, and cafés. The mining town atmosphere faded away. When the aerial coal transport cableways were shut down in 1985, few reminders of coal mining were left.

- 1/1

17. of may in Longyearbyen. Photo: Anne Lise Klungseth Sandvik/Svalbard museum

A community in transition

At the end of the 1980s the coal industry was once again in crisis. Norway was spending over NOK 100 million to subsidise Store Norske. Longyearbyen needed support from additional employment sectors. Ambitious efforts began to create new, profitable businesses, especially within tourism, trade, and services. Responsibility for infrastructure and town operations was transferred from Store Norske to a separate entity: Svalbard Samfunnsdrift AS. Research activity spiked both in Longyearbyen and in Ny-Ålesund. Higher education was prioritised and UNIS, the University Centre in Svalbard, was established in 1993. The Norwegian and foreign students this attracted were a valuable addition to the local community. These new activities more than compensated for the loss of jobs in the mine, and within 10–12 years, Longyearbyen’s population had nearly doubled. During the 1990s, the town blossomed into a modern, diverse family community. Longyearbyen offered public and private services greatly surpassing those available in towns of similar size in mainland Norway. The town’s transformation since 1990 is unparalleled in Norwegian history.

The Local democracy

In 2001, the Norwegian Parliament decided to implement local democracy in Longyearbyen starting 1 January 2002, and Longyearbyen lokalstyre (Longyearbyen Community Council) was established. At the same time, the Community Council took over Svalbard Samfunnsdrift.

Once established, the new Community Council assumed responsibility for many tasks within the district of Longyearbyen such as zoning, roads, water and schools. Many of these resembled the responsibilities of a municipality in mainland Norway, but certain regulations do not apply in Longyearbyen. These include the right to geriatric care, social security, and special adaptation for people with disabilities.

On 19 November 2001 the first election to the Community Council was held and 15 representatives were elected. The Cross-Political Joint List won eight seats, giving it an absolute majority. Labour won six seats and the Conservatives one. The old Svalbard Council was disbanded 31 December 2001 and Longyearbyen Community Council took over from 1 January 2002.