English and Dutch merchants had been trading in the White Sea region since the late 16th century. We assume that Russian merchants in Arkhangelsk learned of the whaling around Svalbard from them. Peter the Great became Tsar of Russia in 1689. In 1697 and 1698 he took educational trips to the Dutch Republic and England, where he also heard about whaling at Svalbard. Peter the Great wished to transform Russia into a European superpower, and promoted the development of Arctic sea hunting, trade, and shipping in northern Russia. He visited Archangelsk several times, encouraging tradesmen and shipbuilders to invest in hunting and whaling in the northern seas. The Russian government established a system in which private trading companies could hunt and trap in Arctic waters under state protection.

In 1703 and 1704, a monopoly was created for development of whaling, Arctic sea trapping, and fisheries in the north. The aim was to create a solid economic foundation for the risky business of whaling. Arctic hunting and trapping would be a tool to benefit whaling, which in turn would help increase foreign trade. Whaling was a disappointment, but trapping was more successful.

Russian winter trapping in Svalbard in the years from 1704 to the 1840s was an important part of the resource extraction from the Arctic. Hunting and trapping in northern seas and the Pomor trade also had links to the Russian fisheries along the coast of Finnmark. The Pomor trade involved exchange of grain for fish. When the trade monopoly ended in the late 1700s, the Pomor trade gained legitimacy. It appears that Russian trapping in Svalbard and the northern seas evolved in parallel with the general upswing in Russian shipping, of which the Pomor trade was a part.

WALRUS HUNTING

Walrus hunting was mainly done on land, but sometimes on sea ice. The hunting grounds were gruesome sites where large parts of the herds were slaughtered. The walrus is a massive animal with thick skin and is difficult to kill. Most walruses were slain on land as they lay in herds at their preferred haul-out sites. They would gather in the tidal zone, on beaches or low promontories near deep water, where it was easy to get back into the water quickly. The walruses would lie packed together, sometimes partially on top of each other. Cautiously and in silence, the Russians would approach the haul-out site in small boats. Then they leapt ashore and killed the walruses that lay closest to the water. In this way, they created a barrier of dead animals that blocked the path of others trying to flee. Walruses move clumsily on land, and the Russians could take their time killing their prey.

- 1/1

Walrus slaughtering site. Photo: Svalbard Museum

The wooden clubs the Russians used to beat seals to death were of no use against a walrus. An 18th century rifle was equally useless for killing or injuring a walrus unless one managed to shoot it in the forehead or temple. Therefore the preferred weapons were sharp lances, harpoons, and iron spikes. They could be up to 70 cm long, attached to 2-to-3-metre long wooden poles. The quickest way to kill a walrus was to stab it through the heart or kidney. But walruses have thick skin with many folds. So the hunters looked for stretched-out skin. They would trick the walrus into lifting and turning its head, thus tautening the skin on its neck.

Walruses were also hunted on the ice. The Russians used multiple small boats, each crewed by two or three hunters, to locate the herds. Then they either rowed or dragged the boats over the ice towards the prey, ideally with the wind at their backs. Walruses that took to the sea were caught with barbed lances resembling boathooks. A harpoon line was attached either to the boat or to a lance thrust deep into the ice. This prevented loss of the walrus cadaver.

LIFE AT A 16TH CENTURY RUSSIAN OVERWINTERING STATION

Provisions

The Russians usually brought along enough provisions for eighteen months: rye flour for baking bread, barley and oat flour, peas, flaxseed oil, honey, fermented milk, salted meat, and salted cod and halibut. They obtained fresh food by hunting.

Clothing

The Russian hunters came from the area around the White Sea. They wore the same clothing in Svalbard as they did at home: undershirt of leather and outerwear of reindeer pelt. On their heads they wore fur hats that extended over the back of the neck, and on their hands, sheepskin mittens. In winter they wore boots made of reindeer skin. The rest of the year they wore high boots with felt soles.

- 1/1

Pomor-cross exhibited at Svalbard museum Hege Anita Eilertsen | Svalbard museum

Everyday work

The Russians spent their spare time crafting goods to sell or for their personal use. They made shoes and clothing, did carpentry, forged tableware, and carved playing tokens for board games. They looked after the spoils of previous hunts and prepared gear for future hunts. They wove nets and made floats; they sharpened lances, fishhooks, knives, and harpoons, and made wooden sheaths for them.

Household goods

The Russians used wooden plates, glazed and unglazed ceramic pots, wooden knives, spoons made of wood or horn, ceramic oil lamps, and game boards with tokens. The furniture consisted of stools, tables, shelves, pegs, and bunks along the walls. Furs served as bedding.

- 1/1

Reproduction of a russian icon. Hege Anita Eilertsen | Svalbard museum

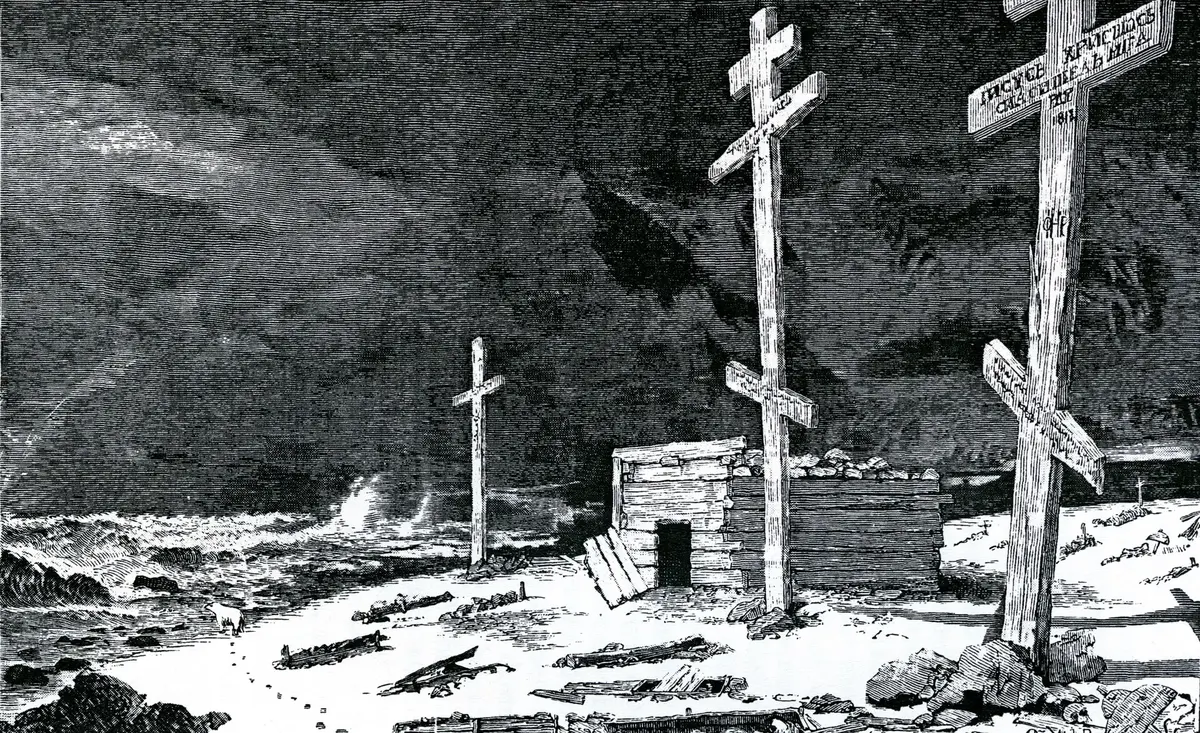

The trapping station

The buildings were constructed of saddle-notched round timber or horizontal planks. The materials were often brought ready-cut from Russia. Sometimes they used local driftwood. The roofs were flat, made of planks covered with gravel and rocks. The rooms had small windows and a low door. The main station comprised several buildings standing so close together that they almost functioned as rooms in a single building. These ‘rooms’ appear to have had distinct functions: sitting room, bedroom, sauna, hallway, storeroom, and workroom. They were heated with a chimneyless woodstove. Outside there was a courtyard with no roof, but with a windbreak wall. Here they stored hunting gear, provisions, the spoils from previous hunts, tools, boats, and driftwood for fuel. The secondary stations were smaller but built and furnished in the same way as the main stations.

The annual cycle

The Russians arrived in June or July. When they got to the station, the new arrivals relieved the old crew, and the main station and the secondary stations were put in order for winter. Sometimes the main station was expanded, new secondary stations constructed, and a new cross erected at the station. These crosses were three to four metres tall and had three crossbeams. Often several would be grouped together. They may have been used as navigational aids. In late autumn and the darkest part of winter, the men spent much time working indoors and playing board games.

When light returned, the hunt began for furs, marine mammals, birds, arctic charr, eggs, and down. The trappers’ year ended in August, with preparations for the journey home.