In the 19th century, the archipelago was frequently visited by trappers, scientists, and adventurers. Many did this as a profession, while others pursued it as a hobby. James Lamont, a wealthy Scottish lord, visited Svalbard in 1858, 1869, and 1871. With his own yacht, he organized grand hunting expeditions to Svalbard and returned home with large hauls, which he then sold. However, he differed from Arctic skippers and trappers in that this was not his occupation — he was a trophy hunter.

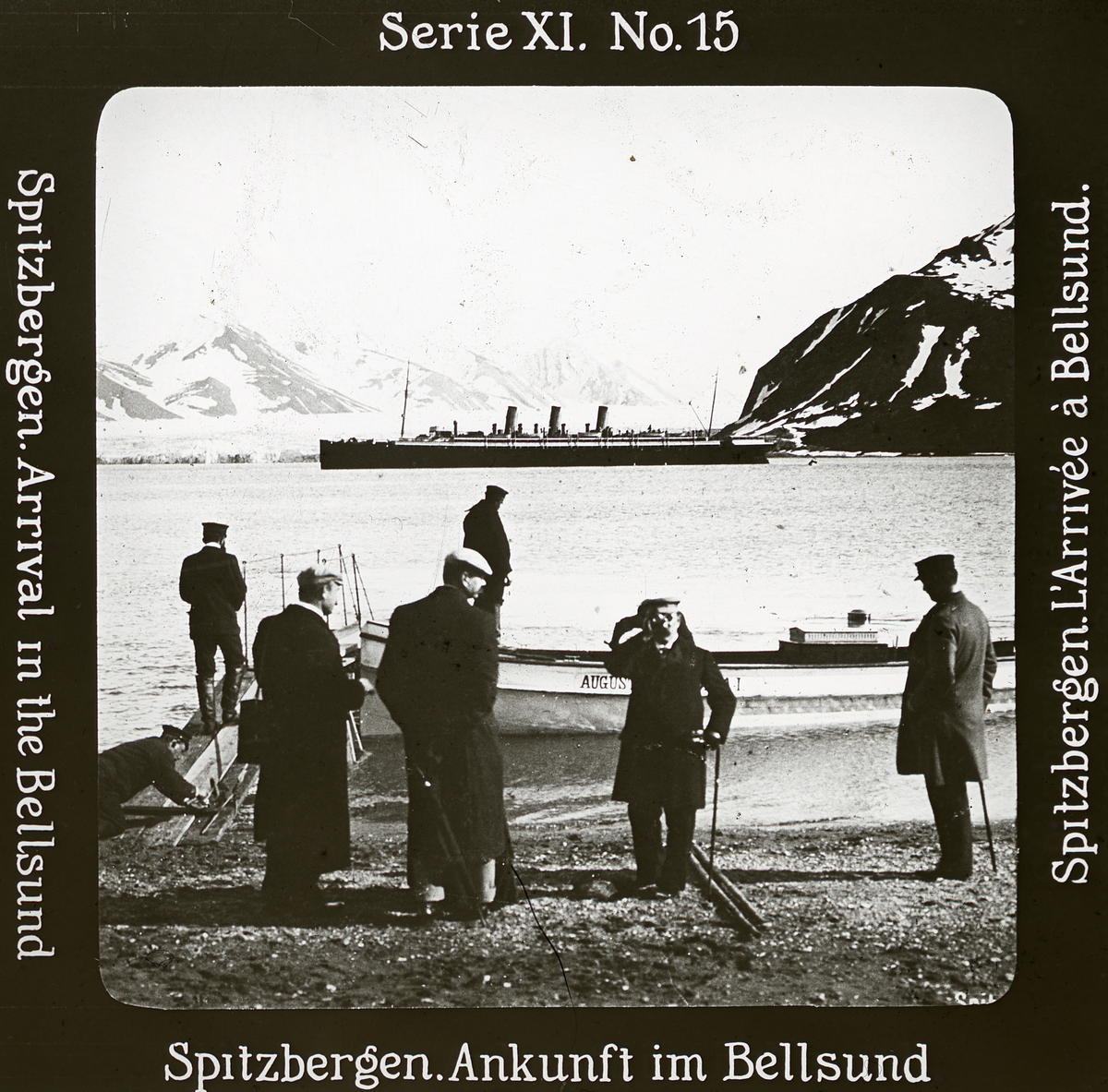

Not long after, large luxury cruise ships like the Auguste Victoria arrived, allowing members of the European and North American upper class not only to admire the landscape but also to observe real trappers and explorers from the comfort of the deck — without giving up the modern luxuries they were used to. At Hotellneset, where Svalbard Airport is located today, a hotel was built in 1896 by the Vesteraalens Steamship Company. The hotel even had its own post office, so travelers could send letters home. This is where John Munro Longyear first encountered Svalbard as a tourist in 1901, and the sight of coal seams soon brought the mining magnate and industrialist back again.

Some companies organized hunting or sporting trips, and when mining was shut down in Ny-Ålesund, a hotel — the Nordpol Hotel — was established to maintain activity in the abandoned mining town. Still, it took time before tourism reached the scale it has today.

When the state took over ownership of Store Norske in 1976, Longyearbyen was to become a “normal” society, and the mining company’s role was to focus on mining. Falling coal prices also meant that the local community needed more sources of income, but tourism was seen as both unprofitable and a threat to Svalbard’s fragile nature. With the rise of the environmental protection regime starting in 1973 — when over half of Svalbard was protected — such activity was initially considered incompatible with Norwegian Svalbard policy. The authorities therefore sought to limit tourism as much as possible, but with little success.

When the airport opened in the mid-1970s, tourists flocked to the islands — even in the absence of local hotels, restaurants, or activity providers. This unorganized tourism put pressure on the environment, the local community, and the Governor of Svalbard’s rescue services. But under the terms of the Svalbard Treaty, there was little that could be done to limit it, apart from placing restrictions on hotel construction.

By the second half of the 1980s, the need for new industries became greater, and the authorities acknowledged that it was better to organize tourism and benefit from it than to resist it. An organized tourism industry would not only create new jobs but also ensure that tourism activities took place under controlled conditions and in a way that was compatible with environmental protection.

Companies like Spitsbergen Travel A/S were established in the 1980s with the goal of further developing the tourism industry on Svalbard. Environmental regulations and certified guide training programs were created, and by the 1990s, everything was in place to invest in tourism as a viable industry. The result is the Longyearbyen we know today — a vibrant adventure hub with world-class hotels and restaurants, where the population doubles as soon as a cruise ship docks.