The settlements in Svalbard were not directly affected by Germany’s invasion of Norway on 9 April 1940, the fighting that ensued, or the capitulation. After the Norwegian government and the royal family fled to London in 1940, operations in Svalbard continued as they had when the war started.

This changed after Germany invaded the Soviet Union 22 June 1941. In August–September 1941, Allied forces evacuated everyone from Svalbard (except Anders Halvorsen, a pacifist who hid during the evacuation and was for some time the only person in Svalbard). First, all Soviet citizens were sent to Arkhangelsk on the cruise ship Empress of Canada, which then returned to transport all Norwegian citizens to Great Britain. All coal that had already been mined was set on fire so it would not benefit the Germans.

Both the Allies and the Germans needed weather data from the Arctic. This information became even more important after August 1942, when the United States and the United Kingdom started sending weapons and supplies with the Arctic convoys. This ‘Lend-Lease’ traffic was crucial to the Soviet war effort on the eastern front. The convoys had to navigate between Svalbard and occupied mainland Norway, where the Nazis had stationed large numbers of planes, ships, and submarines to stop this traffic.

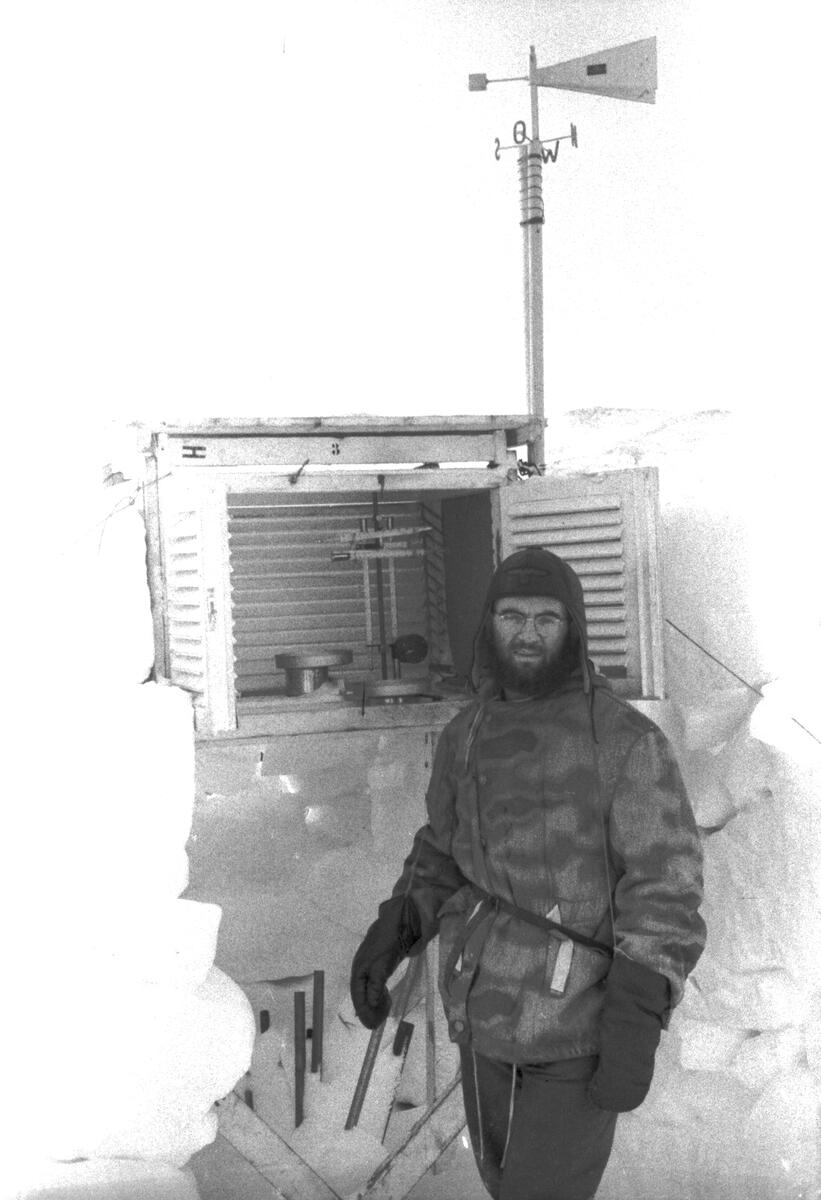

The weather impacts both aeroplanes and ships, so pilots and captains needed weather forecasts. At the time, there were no satellites or other means of monitoring the weather: manned weather stations in Svalbard were vital to forecasting the weather over the Barents Sea. The Germans soon realised that everyone had been evacuated from Svalbard by September 1941, and they established their first weather station ‘Bansö’ and a winter airstrip in Adventdalen just outside Longyearbyen.

Operaton Fritham and Zitronella

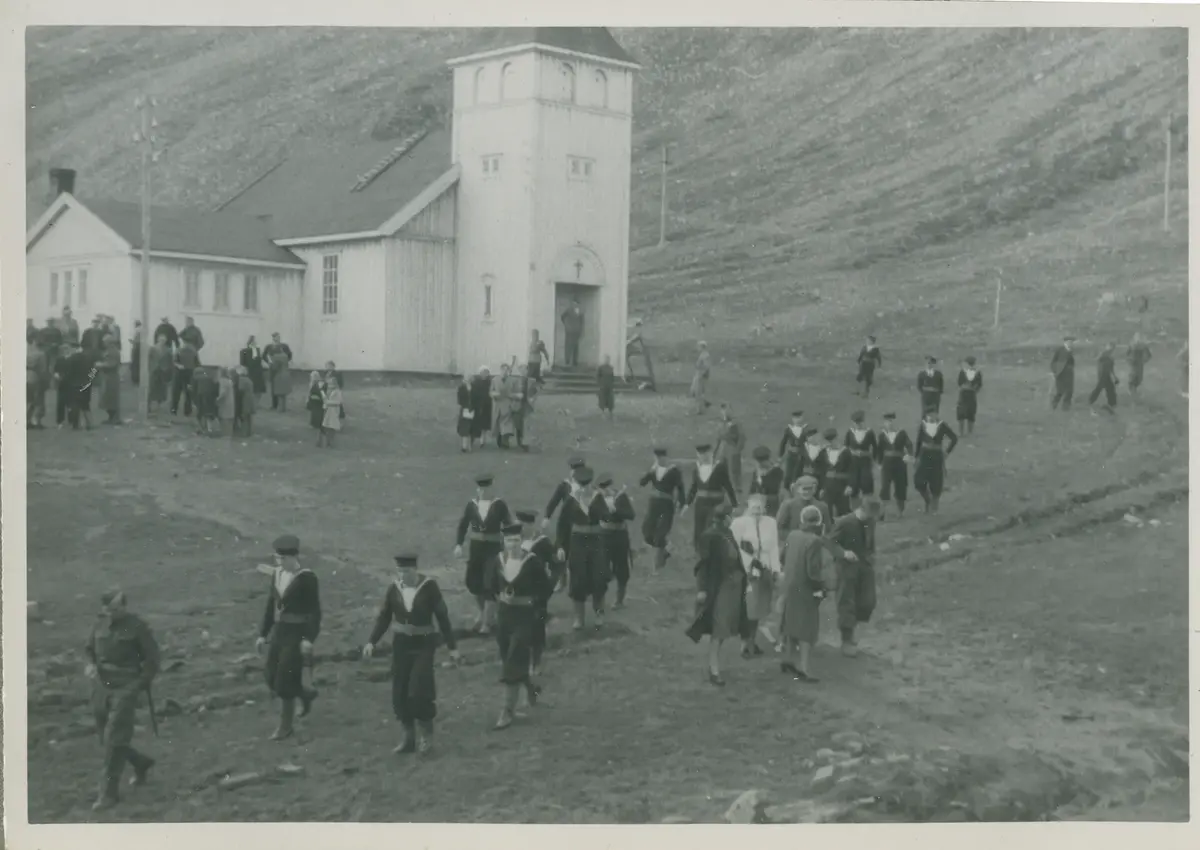

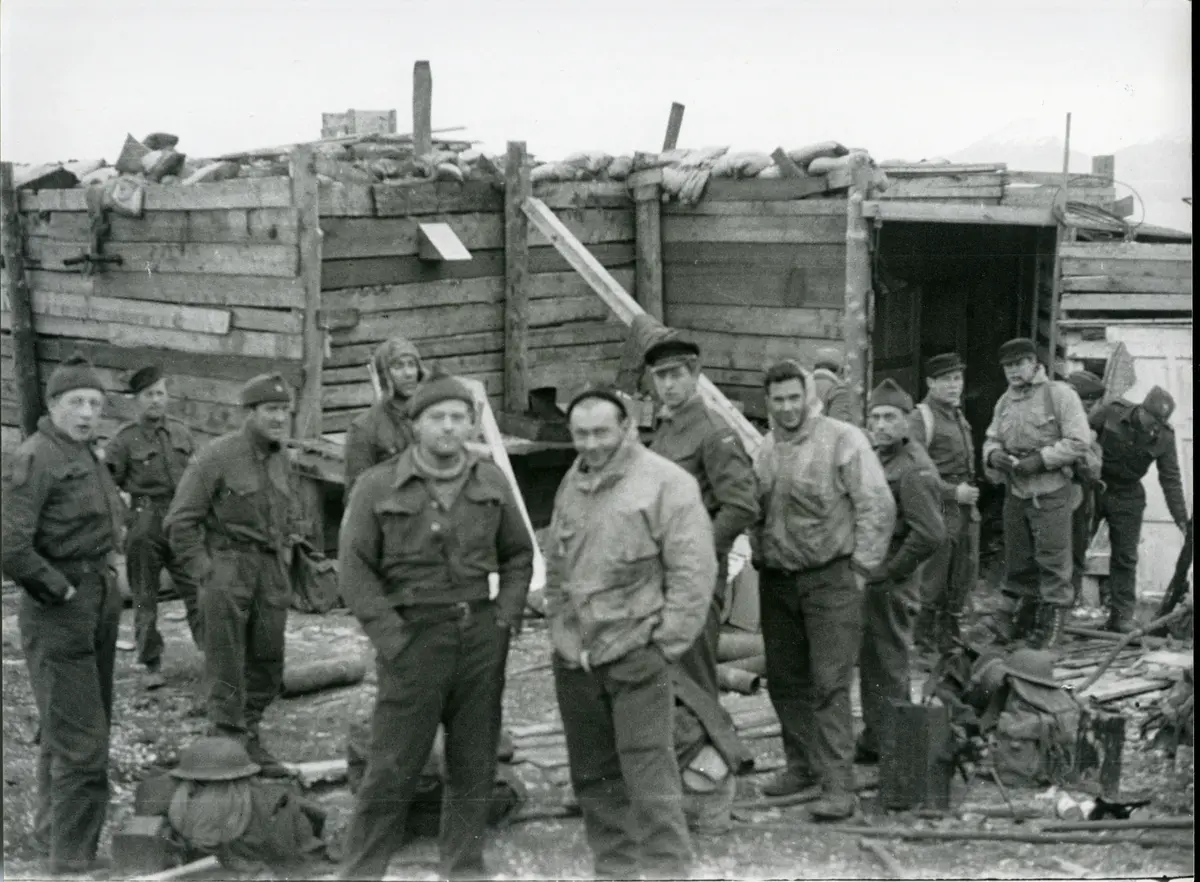

In May 1942, a small Allied force came to Svalbard with the vessels Isbjørn and Selis to reclaim the area around Isfjorden. The operation was called ‘Fritham’. The ships the force arrived in were spotted by the Germans and sunk in Grønfjorden. Many perished, among them the head of the operation, Einar Sverdrup, who had also been director of Store Norske. The survivors established a foothold, first in Barentsburg, and eventually in Longyearbyen.

In response, the Germans launched operation ‘Zitronella’ in September 1943, sending the battleships Tirpitz and Scharnhorst to Svalbard. These ships shelled and burnt the mining towns of Barentsburg, Grumant, and Longyearbyen. Later, Svea and the rest of the buildings in Van Mijenfjorden were destroyed by a German submarine.

After that, the war in Svalbard was relatively subdued. A small Norwegian garrison numbering 60–120 men remained in the region of Isfjorden until the end of the war. They made use of existing houses and cabins, but also constructed a few new ones, one of which is Fritham at the southern end of Todalen. The Germans relocated their weather stations to where they could be undisturbed, but maintained several active stations in Svalbard throughout the war.

After eastern Finnmark was liberated by Soviet forces in October 1944, Svalbard became a pawn in international politics, although nobody in Svalbard knew it at the time. The Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav M Molotov demanded of his Norwegian counterpart Trygve Lie that Svalbard should be under joint Norwegian–Russian administration after the war.

WWII CULTURAL HERITAGE IN SVALBARD

Svalbard holds many culturally important relics from WWII, including charred pilings, gun emplacements, cannons, and the remnants of a German aircraft.

There are also several traces of old German weather stations. When the Germans withdrew from Svalbard in 1945, most of what they left behind was torched, apart from Haudegen on Nordaustlandet.

Haudegen weather station was erected in 1944. Like all the other German weather stations, it was deliberately placed as far as possible from potential Allied activities. Its eleven-man crew was equipped to spend 18 months in isolation. They were not evacuated until September 1945, several months after the war ended. Haudegen Station was left intact, along with a lot of equipment.

The main structure and an outbuilding remain standing. Many loose objects from when the station was operating lie scattered in and around the buildings. These are all protected cultural heritage relics and may neither be removed nor disturbed. At the top of the ridge behind the station, the remains of an emergency radio station can be seen; there are also four depots and two cairns in the area.