The years between 1906 and 1915, when ACC ran the mines, is often called ‘the American era’. A lot of money was invested, and gradually an entire little mining community emerged. A couple hundred people were employed on an annual basis. Most of the labourers came from Norway and Sweden, whereas the administrators were usually British or American. However, these early years were characterised by discontent, strikes, and unrest. The labourers lived in primitive conditions, sleeping in bunks, four to a stall, in huge barracks holding 32 or 64 men each. Hygiene was poor owing to the scarcity of water; the menu was basic and monotonous, especially in spring before new provisions arrived. The labourers probably persevered only because the pay was better than what they could get for mining and construction jobs on the mainland.

Norwegian interests take over

In 1916, ACC and all properties owned by the Americans were sold to Det norske Spitsbergensyndikat – the Norwegian Spitsbergen Syndicate. The Syndicate also bought coalfields in Grønfjorden, and in November 1916, Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani AS (SNSK) was founded. In the winter of 1917–1918, the company employed over 180 men; in addition 34 women and children spent the winter. By 1920 the number had increased to 289, including 37 women and children.

- 1/1

Photo: Sigurd Andreas Rasmussen, Svalbard museum

In 1925, Norway assumed sovereignty over Svalbard. The effect on the community in Longyearbyen was minimal. The privately owned SNSK largely governed and ran Longyearbyen as a ‘company town’. It was not until the 1960s that the residents began demanding modernisation and ‘normalisation’. The transformation gained momentum in the mid-1970s when Norwegian authorities adopted an active Svalbard policy. The goal was to turn Longyearbyen into a community for families, like other Norwegian towns. The opening of the airport in 1975 was a turning point: isolation in winter became a thing of the past. In 1976, Store Norske was nationalised; thus the management of Longyearbyen was also transferred to the state.

Frozen fjords, isolated communities

In autumn, as the departure of the last boat of the year approached, Svalbard’s residents grew restless: was it time to leave after all? Some decided at the last minute, and left. Others had no choice but were obliged to leave. Employers evaluated their workers in secret and sent away any who were deemed physically, mentally, or socially unfit to spend the winter.

- 1/1

S/S "Forsete" in Adventfjorden 1926. Photo: Albert Edwin Nicholls, Svalbard museum

The vast majority of the employees had left their families behind on the mainland. The communities that emerged on Spitsbergen were not intended for families. They were masculine societies where the workers lived in barracks.

Christmas was a special time in the isolated community. Longyearbyen got its own church and priest in 1921, and the church was never as packed as during the Christmas service. Packages that had been hidden away since arriving from the mainland in autumn were brought out, and telegrams arrived from family. For those who received no telegram, isolation became an extra heavy burden.

The Russian communities offered the only direct outside contact. They lay a bit further west in Isfjorden. Grumant was closest; Barentsburg further away.

- 1/1

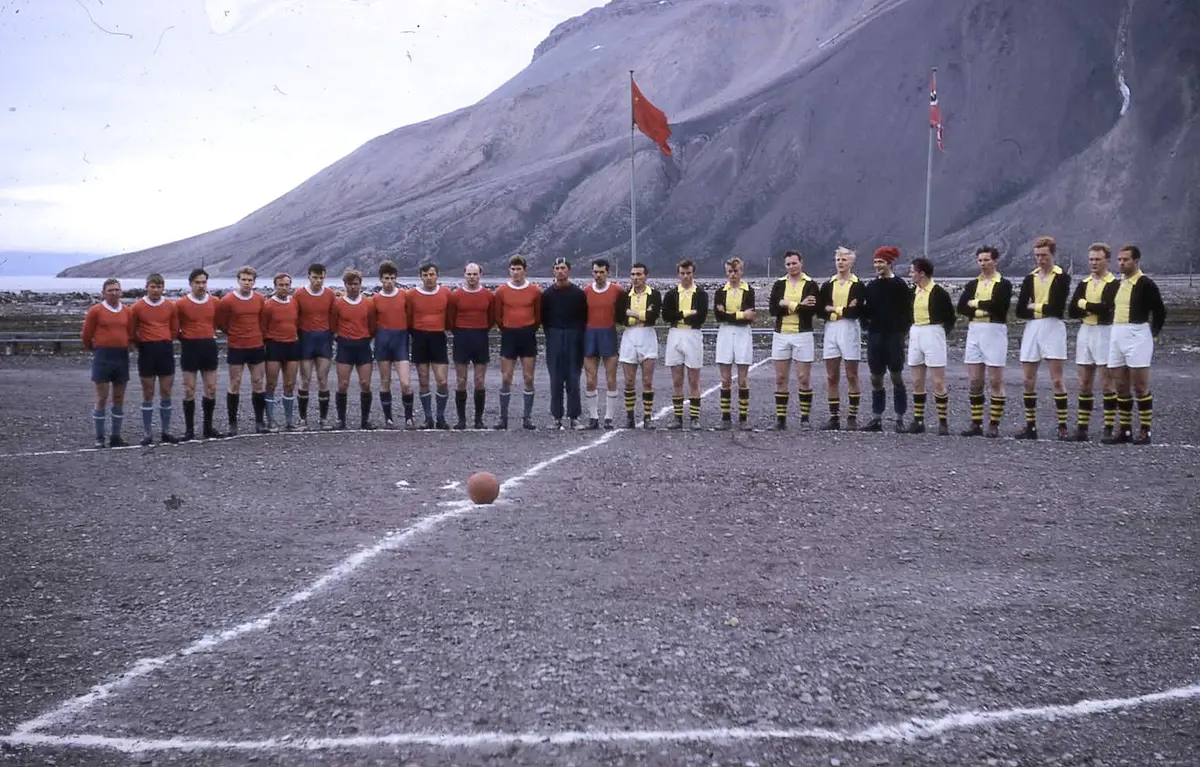

Sports exchange in Pyramiden 1964. Photo: Hans-Jacob Hallvang/Svalbard museum

When the light returned it was possible to ski there. Between the two World Wars, the three communities began having sports exchanges. These annual events continued, interrupted only by WWII and the invasion of Czechoslovakia. The advent of snowmobiles in the 1960s further increased the frequency of contacts between neighbouring communities in Isfjorden during winter.

Open sea, open society

The arrival of the first boat of spring marked the end of winter’s isolation. The ice covering Isfjorden usually broke up in May or June. Summers were hectic. Coal ships docked and sailed. Work in the mines was partially curtailed so the miners could help load the winter’s production. Goods were loaded and unloaded. Letters arrived and a postman ran a ‘post office’. There was fresh food on the table. Some of those who had spent the winter sailed for home and new people arrived. In summer, the community was in a state of flux. One consequence was that sports teams, organisations, and unions ceased to function as long as the fjord was open and the sunlight was strong. Research expeditions and tourists contributed to the feverish activity.

The power was in the hands of the mining companies; the Norwegian state was represented solely by the Governor (Sysselmannen). The mining companies controlled not only the mines, but also housing policy, supplies, and communications. But wages were considerably higher than on the mainland; this attracted workers to the mines in the Arctic.