Read more about the mining towns

No man’s land

The influx of tourists, geological mapping, and polar expeditions at the end of the 19th century raised awareness about Svalbard. That also sparked hopes of making money off the archipelago’s mineral resources, briefly prompting a euphoric gold rush mood.

Between 1989 and 1920, more than a hundred land claims were made. The total area claimed exceeded that of Svalbard. The archipelago was carved up and distributed among private interests. A simultaneous ‘prospecting fever’ in northern Norway may have spread to Svalbard.

- 1/1

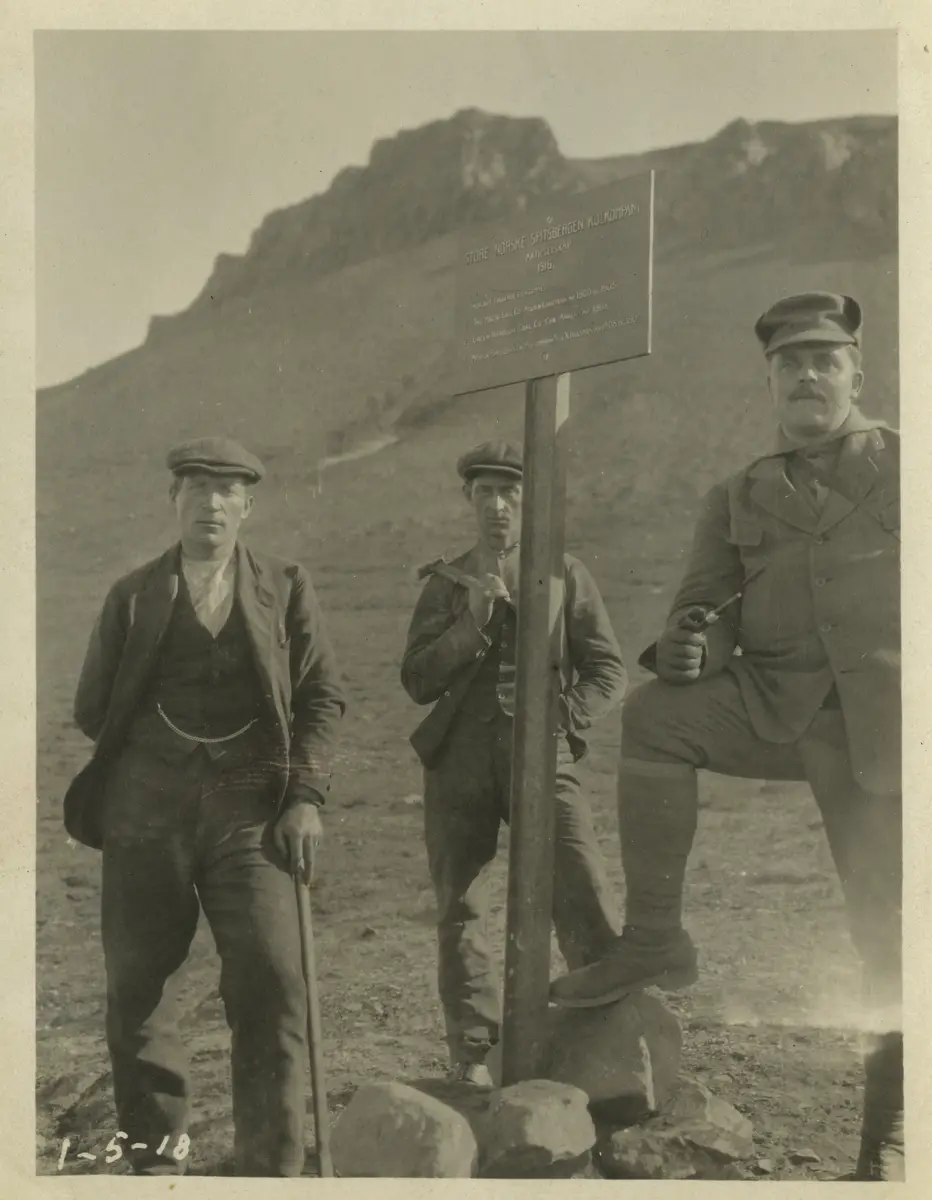

Three men next to Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani AS' annexation sign in 1918. Svalbard museum

No rules stipulated how claims should be made. Nonetheless, all claims were marked with signs. They varied in appearance and had different texts, and had to be renewed every year to count as valid. Unclear procedures for laying claims often led to arguments and conflicts. Conflicts were usually resolved on the spot, but a few ended up in court in Tromsø. There were clashes between claimants, and disputes between workers and managers at the new coalmines. The political and legislative consequence was a growing demand for formal administration of Svalbard.

Nationalities

The people who staked claims and declared ownership over tracts of land were a motley bunch. They came from 9-10 different countries. Some were specialists; others merely adventurers. Some knew very little about minerals. Some quickly gave up and sold their claims. Others came north with costly infrastructure only to discover that the mining project they had envisioned was unprofitable. Those who failed left their machines behind when they abandoned Svalbard.

- 1/1

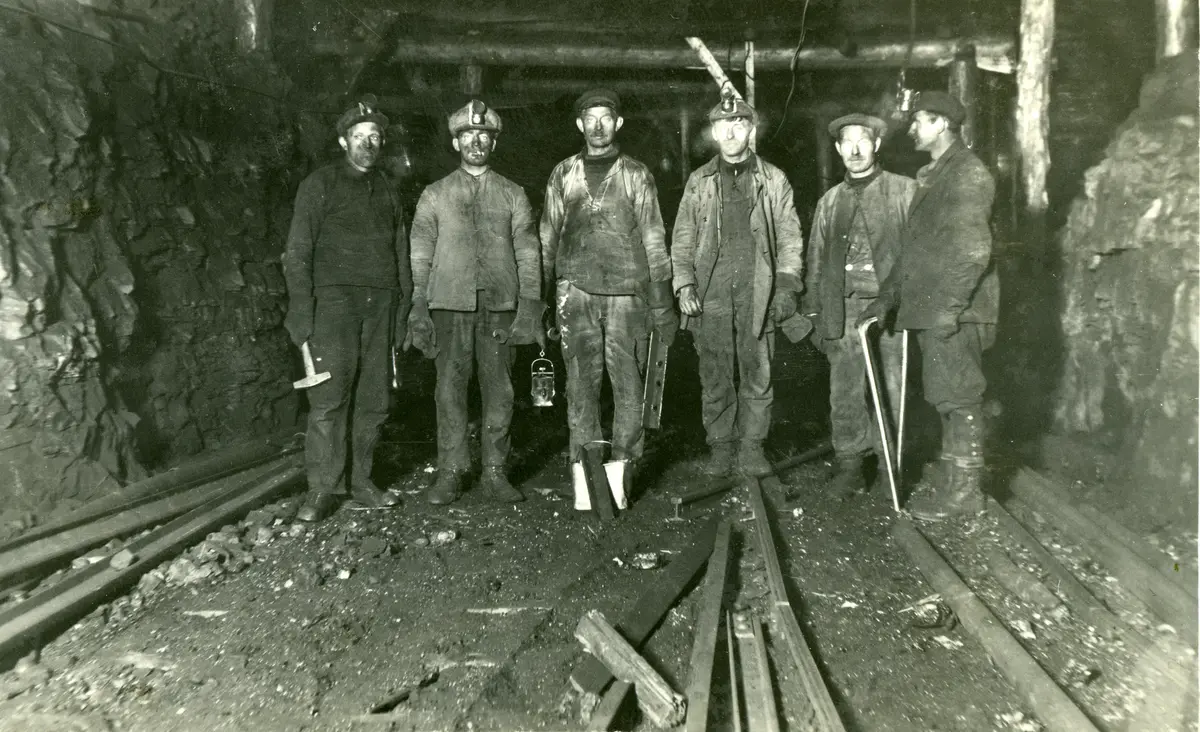

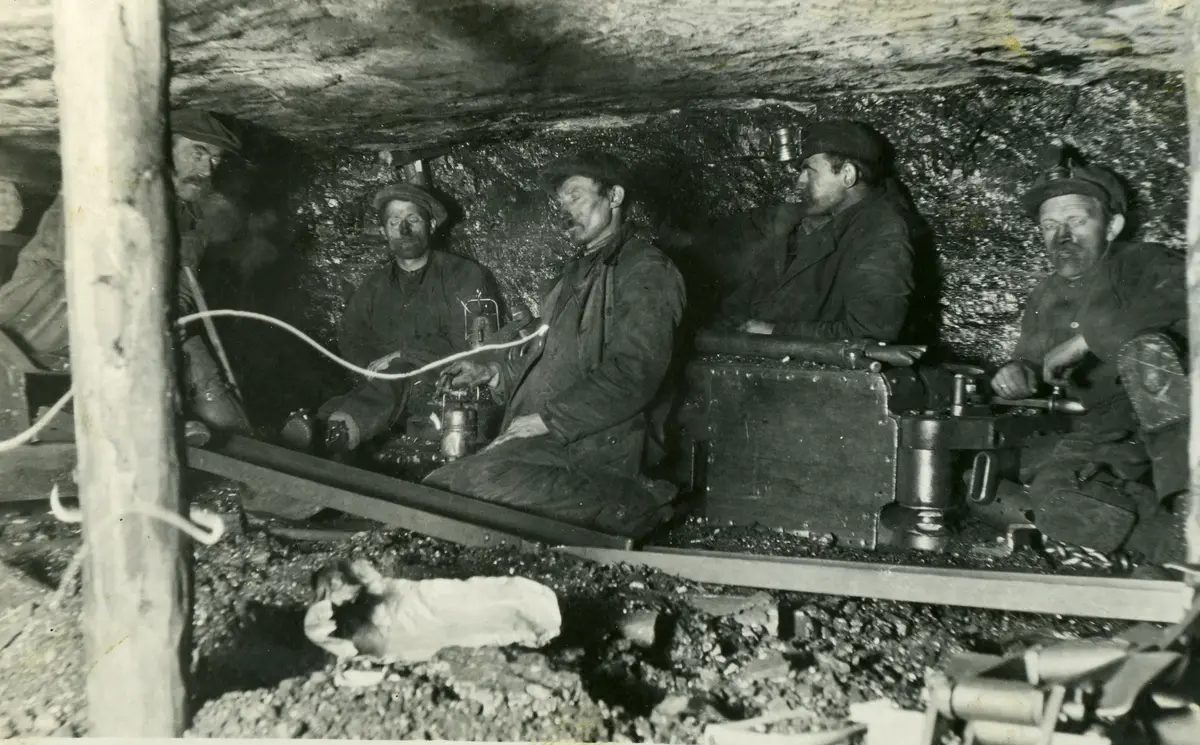

Five men inside a mine. Svalbard museum

Some foreigners claimed areas with viable coal deposits. In places such as Longyearbyen, Svea, Pyramiden, Barentsburg, and Grumant, coal mining continued for a long time