It was the need for coal in northern Russia that initially drew the Soviet Union to Svalbard. The settlements established there had a high standard and modern facilities, which were the envy of visiting Norwegian miners who came regularly for sports exchanges. The workers were hired on two-year contracts and came mainly from the coal-rich Donbas region in eastern Ukraine and from Tula, a mining town south of Moscow. The workers were carefully selected and well paid compared to similar jobs back home. Despite socialist ideals, the Soviet mining towns—like their Norwegian counterparts—were class-divided, and the management lived and dined separately from the workers.

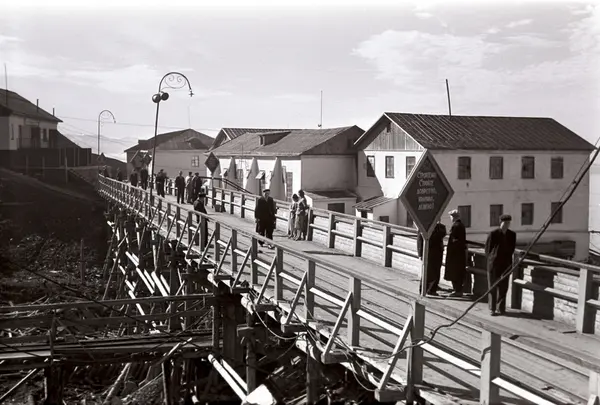

The mining company owned and controlled everything, and up until the 1970s, Norwegian authorities largely refrained from interfering in what happened in the Soviet communities. Compared to Longyearbyen, a greater number of residents in the Soviet settlements were allowed to bring their families to Svalbard. There were schools, kindergartens, hotels, a swimming hall, and a cultural center. To alleviate the effects of winter isolation, self-sufficiency was emphasized, and the communities had their own barns and greenhouses—one year producing as much as 3,700 liters of milk and 5 tons of onions.

Throughout the Cold War, the population in the Soviet settlements was about twice that of the Norwegian ones. Nevertheless, they produced roughly the same amount of coal, despite having a higher degree of mechanization, and the operations were likely not very profitable. This has fueled speculation about the Soviet Union’s true motives for its presence, with some claiming the mining communities were a socialist prestige project, and others suggesting they served as a foothold for seizing control of Svalbard in the event of war.

Today, the properties remain under Russian ownership, and only Barentsburg still has a permanent population. The number of residents there has declined significantly, and today fewer than 400 people live in the town. Coal mining continues, but following Longyearbyen’s example, there are now efforts to develop tourism and research to sustain future operations.